Reviews

An exhaustive, intellectual and entertaining history of American knitting, Knitting America takes knitting from the first Colonies in the 1600s to present-day knitting.

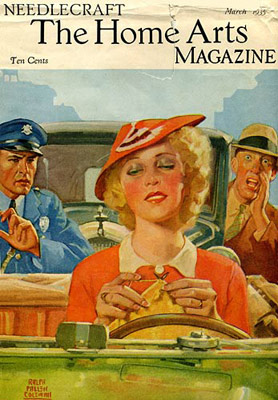

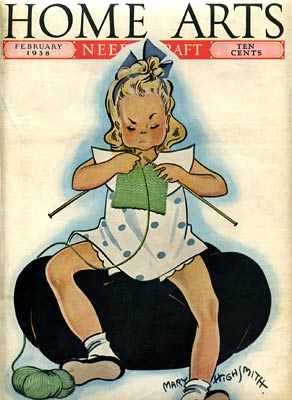

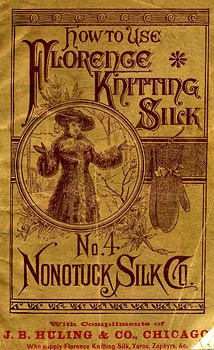

It’s a book to read from cover to cover. The history is fascinating, but the illustrations are absolutely captivating—photographs, historic paintings, yarn ads, patterns books. I kept trying to read the book from start to finish and getting sidetracked with all the visuals. My advice is to pore over the photos and drawings before trying to read the words.

knitty.com

This meticulously researched look at knitting America, from Colonial times to the present, earns an honored place on the bookshelf next to A History of Hand Knitting and No Idle Hands. Thing is, it’s so visually interesting, you’re going to want to leave it out on the coffee table instead. The illustrations tell the story as vividly as the text.… It’s a must-have for fiber historians. This meticulously researched look at knitting America, from Colonial times to the present, earns an honored place on the bookshelf next to A History of Hand Knitting and No Idle Hands. Thing is, it’s so visually interesting, you’re going to want to leave it out on the coffee table instead. The illustrations tell the story as vividly as the text.… It’s a must-have for fiber historians.

Yarn Market News

When the Lewis and Clark expedition traveled from Missouri to the Pacific Ocean (1803-1806), it explored the territory, cataloged flora and fauna, and met the residents. Susan Strawn has undertaken a similar set of tasks in her examination of the history of knitting in the United States.

Susan writes well, does excellent research, asks good questions, and makes perceptive inferences from the information she discovers. The trick in writing a book like Knitting America is how to manage both broad picture and details. She has successfully balanced these opposing forces while writing a history of the United States as embodied in everyday activities instead of grand actions. She outlined an appropriate and comprehensive set of topics and then brought the ideas to life by digging in archives for photos, letter excerpts, poetry, and other evidence. Her finished work examines human experience in shifting political, economic, and social landscapes by looking at what kinds of people were knitting, what they were knitting with, and what they were making.

Her efforts add up to a terrific account of the roles knitting has played in the U.S.—elegance, function, kitsch, art, and more.  Twenty period knitting patterns, some in their original formats (although freshly typeset) and a few reconstructed by knowledgeable contemporary knitters, give readers a hands-on sense of what knitting was about during different eras. Twenty period knitting patterns, some in their original formats (although freshly typeset) and a few reconstructed by knowledgeable contemporary knitters, give readers a hands-on sense of what knitting was about during different eras.

The 208 pages are crammed with philosophy, sociology, and practicality.I was fascinated to learn how recently gauge indicators have been added to patterns and how long ago circular—and lighted—needles first appeared.I especially enjoyed the descriptions of how knitting fitted into the lives of all kinds of people: Japanese Americans in internment camps during World War II, Native Americans, upper and lower classes in different periods, women and men, boys and girls.

Deborah Robson, Spin-Off Magazine

Page  top top

|

Introduction

This is a book that tells many stories about knitting in America. There are stories about ways that knitting was brought to America and helped provide for the early settlers who spread across the land.  There is a story about the role knitting played in one of America’s first best-selling books, the captivity narrative of Mary Rowlandson. Yarn and knitting needles in portraits of American women tell the story of personal industry and of dedication to home and family. And there are stories too numerous to mention about knitting during America’s many wars, all except one war. The story of American knitting also holds many success stories about immigrants who founded yarn companies and about knitting instructors and designers who carved out careers in the knitting industry. There is a story about the role knitting played in one of America’s first best-selling books, the captivity narrative of Mary Rowlandson. Yarn and knitting needles in portraits of American women tell the story of personal industry and of dedication to home and family. And there are stories too numerous to mention about knitting during America’s many wars, all except one war. The story of American knitting also holds many success stories about immigrants who founded yarn companies and about knitting instructors and designers who carved out careers in the knitting industry.

Bishop Rutt, the eminent historian of hand knitting, wrote, “Information about the history of hand knitting in the United States is hard to find.” I understand how he felt. The history of knitting can be illusive. In the past, knitters have seldom thought to mention such an ordinary, everyday part of life as knitting. And most things that are knit are practical. They are intended to be used up and worn out, not preserved under glass. Writing this book, I learned that knitting was there in the historical record, but I had to look really closely and develop a certain savvy about finding it. Once I did, my dilemma changed from desperate searching to coping with an encroaching avalanche of information about knitting that appeared in the historical record.

Without technological advances in the way our civilization stores and retrieves knowledge, this book would have taken a lifetime to research and write. So many scholarly articles and books have been digitized and can be searched for references to knitting (or “stocking” or “mitten”). In the past, this simple task carried out in a few keyboard strokes would have required extensive travel, research permission, and weeks of reading.  The presidential papers at the Library of Congress, for example, have been transcribed, so online keyword searches uncovered the history of women who sent hand knit stockings to President Abraham Lincoln. More stories about knitters who are otherwise lost to history. The presidential papers at the Library of Congress, for example, have been transcribed, so online keyword searches uncovered the history of women who sent hand knit stockings to President Abraham Lincoln. More stories about knitters who are otherwise lost to history.

Collections of photographs, many digitized and searchable in online databases, often raise more questions than answers about knitters and knitting. Why was a Japanese American woman photographed with her knitting in a World War II internment camp? Similarly, collections of hand knits, seldom digitized or searchable online, hold stories of families who preserved and donated them to museums. If knitting is intended to be used and worn out, why are so many everyday pieces of practical hand knits donated to museums? Without the librarians and collection curators, the fragile stories in the photos and textiles would also be lost to history.

One purpose of this book is to entertain. Another is to consider knitting as a topic worthy of serious research. If you close your eyes and place your finger on any page of this book, you will find a topic for a thesis, dissertation, or biography. More than anything else the stories in this book are intended to honor the craft of knitting and take knitting beyond its often trivialized stereotype. |